Ma'ta Crawford has always gardened and now she's using it to fight food insecurity

Ma'ta Crawford has always gardened and now she's using it to fight food insecurity

![]() Sarah Swetlik Greenville News

Sarah Swetlik Greenville News

Ma’ta Crawford says she’s been gardening since she was "knee-high to a grasshopper."

It’s a warm summer day in Greenville. Birds are chirping and Crawford’s hands are full of ripe peas she’s just picked.

The Greenville native is a third-generation gardener who learned how to care for plants from her grandmother and father. She can’t imagine not being able to put her hands in the dirt and help something grow.

But when Crawford says her life is about gardening, she doesn’t just mean the plants in her yard. She is certainly excited by each new bud or sprout, but she uses gardening as a metaphor for her extensive, lifelong community-based work.

Crawford has worked as a community babysitter. She has headed up the Viola Street Neighborhood Association.She considered opening a restaurant, so she catered her food and saved the leftovers for elderly people who lived nearby.

Today, much of her energy goes to fighting food insecurity in Greenville County, particularly in the 25th county council district. She works on consulting and planning, but she also teaches gardening classes. This year, she published her first coloring book and has started selling small-space gardening kits that people who live in apartments can use to grow fruits and vegetables.

It all stems from her passion for making sure people are fed.

Crawford said she and her sister were raised by their grandmother, who always made sure they had enough to eat.

“It was when we couldn't get to my grandmother that we were hungry,” Crawford said. “My drive and my passion is because I've lived it, and I know how it feels. I don't want a child to have to go to school hungry, or to come home and not have something to eat, or not even have a home to come to when they get out of school, because I was that child.”

Crawford said she experienced food insecurity as a child. Food insecurity occurs when someone has limited or inadequate access to nutritious food.

In Greenville, more than 60,000 people face food insecurity. More than 15,000 of those residents are children, according to data from Feeding America.

Crawford said her garden is a way to combat the lack of access to food.

“As long as I can grow it myself, I have control over what I eat. I don't have any food insecurities because I have a garden,” she said. “That's my security.”

The keeper of the village

Crawford began feeding other people so they wouldn’t have to experience what she went through.

“Because I've worked in the community over 20 years dealing with food and housing insecurities and other social deterrents, last year it just seemed natural. I've always tried to figure out how I could teach other people to garden,” Crawford said.

She began by passing down her family’s love of gardening to her daughter, then eventually to her grandson.

Throughout their lives, she and her children lived in apartments, including some that were income-restricted. Crawford, however, was undeterred in her resolve to teach her kids to garden, no matter how small the space.

“I was one of those parents that tried to steer my children to eat healthy because I knew the value of fresh fruits and vegetables because I grew up on them myself,” Crawford said. “I wanted them to enjoy picking their own food off the vine and putting a muscadine in their mouth, and having it to squish the hot, sweet juice.”

At one apartment complex, Crawford faced eviction for planting tomatoes. She told the landlord she’d plant grass over it, but when he saw her tomato plants, he said she didn’t need to re-plant the grass – he just wanted some of her fresh tomatoes.

“Gardening has been not only a bonding experience for me and my family, but it has opened doors and allowed me to grow with other people,” she said. “I can share the love of gardening with people. I can share fresh fruits and vegetables with people.”

Her passion for helping others extends far beyond food. She also works to ensure people have access to safe, affordable housing.

Crawford’s love for community is where the name “Ma’ta” came from. Her legal name is Tabatha, but she adopted the name Ma’ta when she found her purpose. It’s what she calls her living name.

“Some people say I'm an advocate. Some people say I'm a community liaison. I say that I'm one of the keepers of the village,” she said. “That’s what my namesake means.”

What does food insecurity look like in Greenville?

In Greenville, more than 60,000 people face food insecurity according to data from Feeding America – about 11.5% of the county’s population. Food insecurity tends to affect Black and Latinx residents most, at 26% and 17% respectively. Meanwhile, 8% of white residents in the county are food insecure.

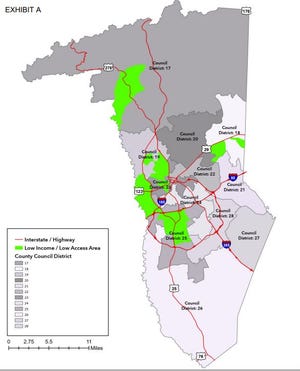

According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food Access Research Atlas, 17 different census tracts in Greenville County had a significant number of residents with low incomes and limited access to a grocery store. In urban areas, low access is considered one mile from the nearest grocery store; in rural areas, low access is 10 miles from a grocery store.

District 25, where Crawford lives, was home to six of those census tracts. Based on 2019 data from the USDA, about nearly 8,200 people met the criteria for both low access and low income in District 25.

One of Crawford’s endeavors to mitigate food insecurity involves serving on the Health Equity Action Leadership (HEAL) board at local nonprofit LiveWell Greenville.

LiveWell Greenville’s Food Security Director Susan Frantz said the board is a multi-lingual group from diverse backgrounds that gather to help guide the organization’s three coalitions: Food security, health equity and active living.

The food security coalition involves a robust group of partners, from faith-based groups to education organizations and food pantries, Frantz said. They work together to identify gaps and potential solutions to healthy food access in the county.

Frantz said one of the biggest challenges to food security in Greenville is a lack of transportation.

Some people may not own cars, or their cars may not be reliable. Others may share a vehicle with several members of their family. Transportation restrictions, especially when coupled with a limited budget, can make it difficult to prioritize finding the healthiest options.

Frantz said she also hears that people struggle with having the time to both purchase and make healthy food. A HEAL board report reiterated that the largest barrier to healthy food habits was time.

“People who are struggling with food insecurity are likely working a lot of hours, and when coupled with the issue of transportation, it's hard, often, to get to a food pantry when they're open,” Frantz said. “It might be open Tuesday through Thursday, 9 a.m.-1 p.m., but if you can't get there at that time or if you have to take off work to get to the food resource at the time that they're available, that's really challenging for people as well.”

The coalition focuses on “action circles,” or a specific project or goal, to help meet the needs of people facing food insecurity in Greenville. Currently, the coalition has eight action circles.

One of those circles is identifying food pantry resources and opportunities to make them more accessible. This year, the coalition is focusing on District 25, which is where Crawford lives. Members of the coalition are researching geographic access to food pantries, but they’re also searching for ways to improve them – Frantz said that could mean partnering with local churches or working together to secure funding. It could also involve training opportunities for workers about how to procure healthy food or ensure people have access to food that are important in their culture.

The coalition also has an action circle focused on community gardens.

Frantz said that the collaboration among all the groups is important.

“When we're all coming together and well connected, then we can figure out ways to collaborate, to share resources to make ourselves more powerful as a whole system, rather than each operating on our own,” she said.

They advocate for policy and systemic change in addition to their on-the-ground work.

Locally, Greenville’s politicians have begun discussing the impact of food insecurity on the county’s population. County Councilmember Ennis Fant, Sr. introduced a resolution in March to create tax incentives for grocery stores considering building in food-insecure areas. Fant, who represented District 25, said that the resolution was referred to the finance committee, where it has since remained.

At the state level, Rep. Wendell Jones, a Democrat from Greenville, was inspired by Fant’s resolution and introduced a similar bill during the 2023-2024 legislative session. Jones’ bill did not make it out of committee.

Will climate change impact food security?

Scientists have said one of the persistent threats to food security is the world’s changing climate. As the earth continues to warm due to greenhouse gasses, crops can suffer, making it even more difficult for people to access healthy, affordable food.

Subsequently, learning how to adapt to growing food in a changing climate is important, said Alex Levine, the Outreach Coordinator for Climate-Smart Grown in SC at Clemson University.

Levine said the goal of the program isn’t to convince people that climate change is occurring, but rather to recognize problems South Carolina’s farmers face and help them use practices that prioritize conservation and biodiversity.

Clemson’s project focuses on peanuts, leafy greens, beef cattle foraging areas and forestland, but Levine said the impact of climate change on food growth extend beyond farmers exclusively. The impact of shifting conditions for crops could hit in the field, in a home garden, or in a resident’s wallet as the food they enjoy becomes more expensive to produce.

South Carolina farmers and gardeners have seen drought, extreme rainfall and flooding, severe heat and fluctuating weather, Levine said.

“It's these conditions that are leading to an increase in food insecurity and that notion of not having access to sufficient food, or that the food is of reduced nutritional quality,” Levine said. “It's a growing problem, and it's directly tied to these conditions which cause failing crops, which cause less nutritional content of the crops that are produced; changing growing zones, so places where they used to be able to rely on a certain crop, they just can't grow that crop anymore. And so that, again, while it's a global issue, is one that hits home right here in South Carolina.”

Levine said that gardening can be a helpful tool in connecting people with the earth and allowing them to understand why climate change can be so impactful.

“Any type of activity that connects you to the earth is going to make you more connected to the climate,” he said. “People are being driven to find solutions, to be more resilient, to be more sustainable, and that's regardless of kind of where you fall on the political spectrum.”

Crawford helps others garden in small spaces

Crawford said she’s seen firsthand how much of an impact working with a garden can have on people, especially children. She said she cares about the earth because it takes care of her, and that’s something she instills in the people who learn from her.

Now, she leads gardening classes, where she teaches people how to care for their plants. Recently, Crawford helped a young boy plant his own strawberries and tomatoes. She said she watched his eyes light up and fill with pride as he took his new plants home.

“It's like a whole new world to them,” Crawford said. “Common for me is extraordinary for them.”

She said she often deals with families who, much like the apartment she lived in, can’t dig in the ground to plant a garden. She was inspired to help other families grow nutritious food, even in small spaces.

So Crawford put together a small-space gardening kit. It includes a felt bag and a two-by-two gardening pad that keeps the entire kit mobile. It includes a robust instruction kit centered around science, technology, engineering, the arts, and math (STEAM) education, and she also makes instructional videos.

The bags can grow up to six plants. Crawford includes instructions on how to keep moisture in the bag so it can be placed inside or out.

She sells the kits online, but she’s also sold them in person. Additionally, she released her first educational coloring book in January 2024, filled with drawings she made for her grandson when he was young. She took him to garden with her often – his vegetable of choice was broccoli – and he would ask her to draw fruits and vegetables when they came back inside. Eventually, she began making copies of the drawings when his friends would come over.

Her grandson told her she should put the drawings in a coloring book. Years later, Crawford was cleaning out her office, and all the old drawings fell out of a manila envelope. She decided to take his advice and make the book.

“This is my way of reconnecting and enjoying the moments that we had together as well,” she said.

Crawford often uses gardening as a metaphor for her life and the impact she hopes to have, including how she approaches change in her community.

“I don't just come with problems. We all know what the issues are,” she said.

She said growth is a group effort.

“You need the sun, the water, the fertilizer and love, and the good dirt,” she said.

Sarah Swetlik covers climate change and environmental issues in South Carolina's Upstate for The Greenville News. Her position is funded by The GreenSouth Foundation. Reach her via email at sswetlik@gannett.com or on X at @sarahgswetlik.